Presentation Tip: Eliminate 75% of the numbers

Information overload is the single biggest issue in presentations today according to audience members I have surveyed. In my book, Present It So They Get It, I devote a chapter to five strategies for laser focusing your information to avoid the overload problem. One of those strategies is to eliminate data that is not relevant to the message. When I introduce this strategy in my workshops, I suggest that I believe in most cases, 75% of the numbers on a slide can be eliminated. This is met with skeptical looks, especially from financial professionals. How is this possible?

First, I’d like to address how this overload of numbers occurs that leads us to having to eliminate 75% of the numbers. There is a lot of analysis that is done in Excel, and we want to include it in our presentations. Excel is the best tool to do the analysis. The problem comes when we go to put that information into a presentation. It is too easy to simply copy the cells from Excel onto a slide. And that is where we end up including more numbers than are needed to communicate the conclusion of our analysis.

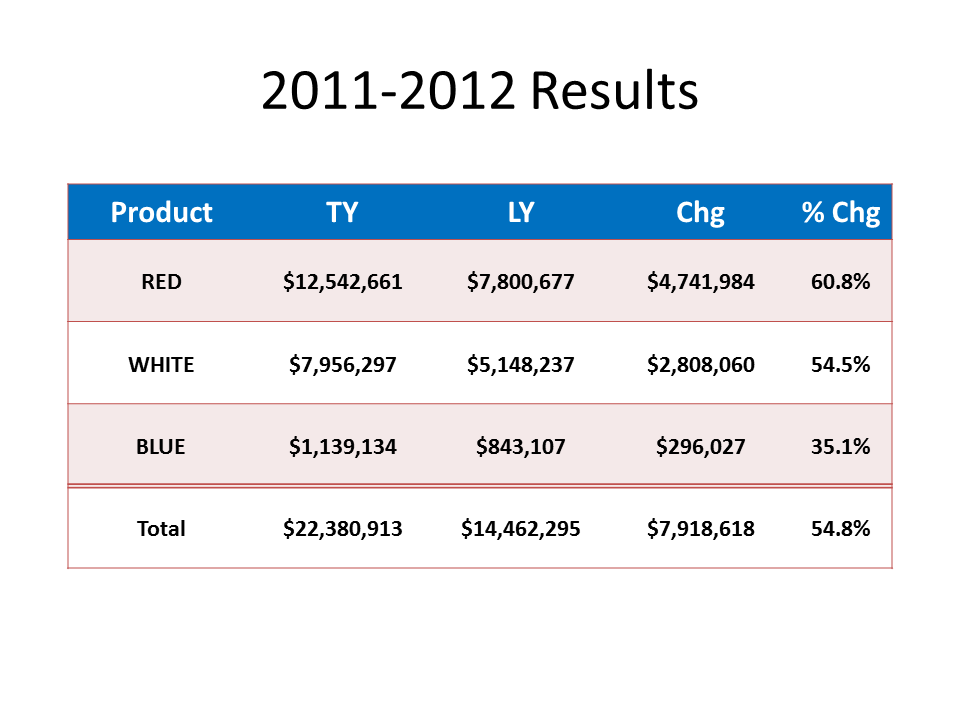

Typically, analysis includes comparing current results to some standard in order to arrive at a conclusion about the performance of a product, group, or territory. It could be comparing current sales to planned sales, current operational productivity to the company goals, or last month’s expenditures to the budget that was approved. Our Excel spreadsheet usually has four columns for each item: the current measured results, the standard we are comparing to, the absolute difference between the results and the standard, and the relative difference expressed as a percentage. When we do a simple copy and paste of these cells, we include numbers that are not relevant to the true message of our analysis.

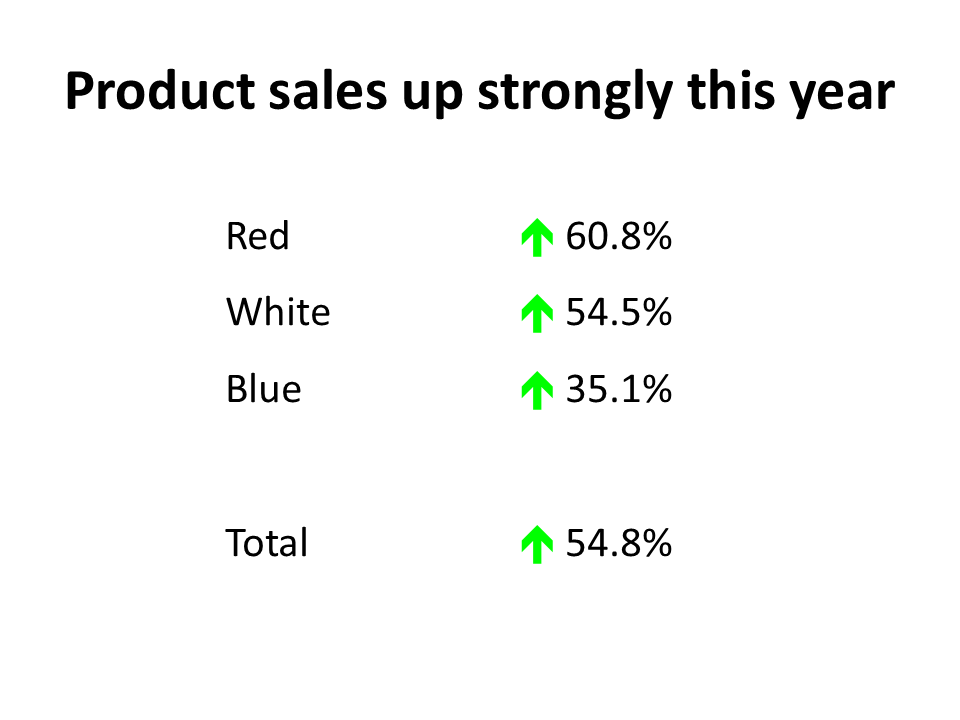

In almost all cases, the audience is most concerned about the performance relative to the standard, the fourth column of our analysis spreadsheet. How did we do compared to what was expected? Were we ahead or behind, and by how much percentage wise? The absolute difference isn’t as helpful because magnitude has to be taken into account. So I suggest that we can eliminate the first three columns, or 75% of the numbers, since they don’t end up helping the audience understand the message.

I also suggest that we can make the percentage difference column more meaningful by adding visual indicators of whether the percentage is above or below the standard and whether that is a positive or negative result (since above standard is not always a good result, especially when it relates to expenditures above budget). I find using the arrow symbols in the Webdings font a good way to add an up or down arrow to a text box or table. You can make the font of the arrow green or red to indicate a good or poor result. And by using a text symbol, it makes it easier to animate the text box.

Here is an example of a slide that had a spreadsheet copied on to it and what the slide looks like when we eliminate 75% of the numbers. Notice how the message is much clearer with less numbers and arrow symbols.

Original slide

Slide with 75% less numbers

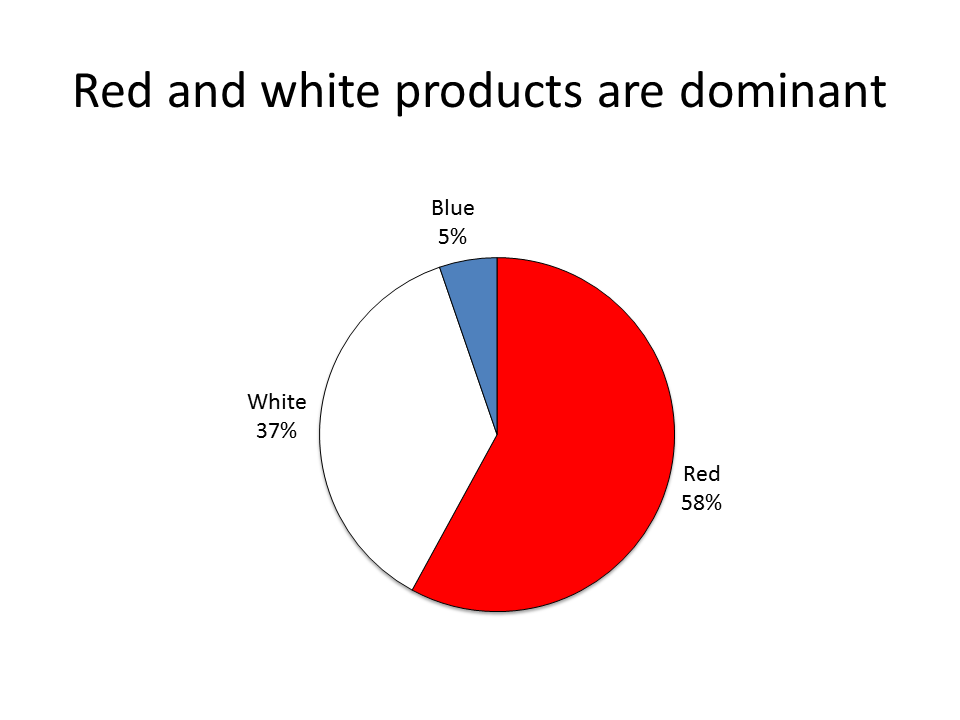

In the above example, some might argue that the split of sales between each of the products is lost when you eliminate the three columns. If you want to make two points from the spreadsheet, I suggest you use two slides. Showing proportions of the total sales between the three products is best done using a pie graph as this example shows.

The next time you want to copy a spreadsheet on to a slide, pause and consider whether you can use these ideas to eliminate 75% of the numbers and make your message clearer for your audience.

Presentation Tip: Proportional Shape Comparison Diagrams

In February I launched a tool on my website that allows you to create diagrams like this:

I refer to this type of diagram as a proportional shape comparison diagram because the size of the shapes allows the viewer to instantly compare the numbers each shape represents. These types of diagrams are popular in print media and are becoming popular in presentations. David McCandless uses a number of them effectively in his TED talk you can watch here.

I think these diagrams work better than a table of numbers because the numbers make the audience do the math to compare the amounts, which is especially hard when the numbers are different by an order of magnitude or more. These diagrams also work better than pie or column graphs because the smaller number almost disappears on the graph due to the graph being limited to measurement in only one dimension. A proportional shape comparison diagram gives you two dimensions to work with and allows smaller numbers to be more easily compared to larger numbers.

The challenge in creating these diagrams has been in doing the calculations. This type of diagram is not built into the PowerPoint graphing function, so you have to do the calculations by hand. To make it easier for you, I created an online tool that does the calculations for you. You simply input the large and small numbers you want the shapes to represent, and the tool will tell you the dimensions of the shapes. The tool calculates dimensions for side-by-side squares, overlapping rectangles (as shown above), and circles that can be side-by-side or overlapping that will fit in most corporate templates. You can also set the maximum dimensions to scale the shapes to fit your template.

Use of the tool is free on my website at www.ProportionalComparisonTool.com. There are examples of the type of diagrams you can create and detailed instructions on how to use the tool. Once you use the tool, you will find it quite easy to include this type of diagram in your own presentations. In the past few months I have used it to show comparisons of customer service contact methods, market penetration in a geographic area, components of the change in financial projections, the reduction in weight of glass containers, the narrowing of investment choices from the full market to those stocks selected for a portfolio, and the results of an e-mail marketing campaign. You can see by the breadth of these applications that this type of diagram can be used effectively in many presentations.

In February I had the opportunity to present this tool to the graphics developers at Microsoft and my fellow PowerPoint MVPs. Everyone thought it was very useful and my fellow MVP Glenna Shaw included it in two articles she wrote for the Microsoft Office Blog. You can see the first of the articles here. People realized that this type of diagram, which used to be only possible with many hand calculations, is now available to all presenters because the tool removes the barrier of the calculations.

Whenever you have to compare numbers that are at least an order of magnitude different, consider using my Proportional Comparison Tool to do the calculations that allow you to create a proportional shape comparison diagram. And pass this newsletter on to others who could improve their presentations by using this type of visual.